6 signs of an emotionally abusive therapist.

It's real, it's violent, and it is soul-shattering. You deserve better.

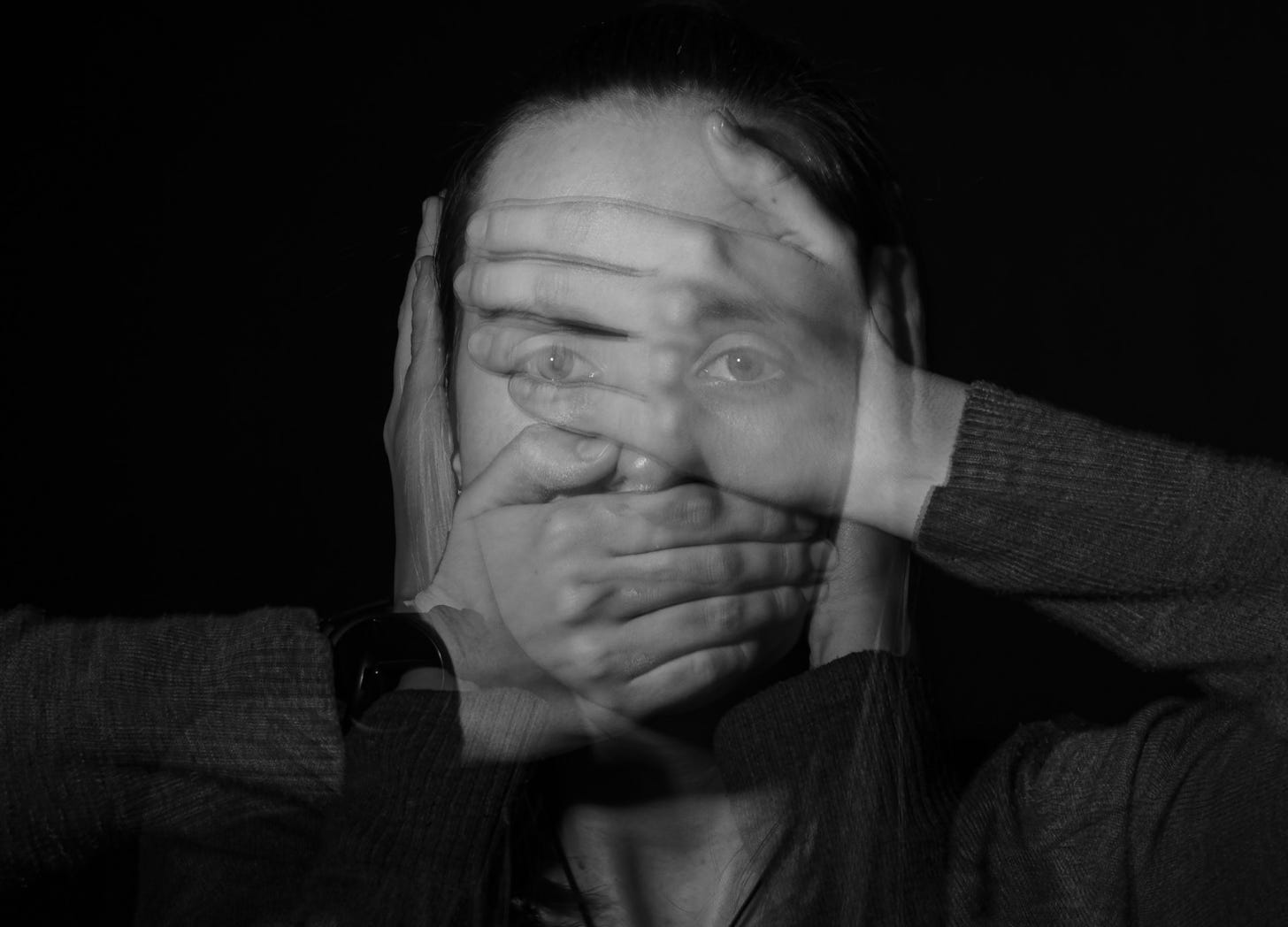

Image by Alex Vamos, via Unsplash.

No matter how many credentials a therapist has racked up, there’s no guarantee that they’ve done enough work on themselves to avoid acting out their pain and trauma on their patients. Training and expertise are only part of the picture, and what’s more important, in my opinion, is that the therapist has engaged in their own work and continues to engage in their own work. We’re all capable of causing harm, regardless of how much empathy and compassion we feel we have, or how pure we believe our intentions to be.

Most therapists, of course, are well-meaning and genuinely want to help the patients who come to them seeking support. But trust in therapists and therapy is undermined by therapists who are predatory, overtly harmful and abusive, or even just poorly trained and overconfident in their abilities. As a two-time survivor of therapist abuse, my intention is not to discredit the field or discourage people from seeking support, but to draw attention to the reality that abusive and harmful therapists exist. The damage they cause can be enormous and soul-crushing, and we don’t talk enough about the harm people are experiencing in therapy.

There’s a significant power imbalance in the therapeutic relationship, and abuse is a product of power. When a therapist abuses or misuses their power, even unknowingly, they can cause serious damage to the person seeking care. This is why the therapist’s responsibility is so great. Not because they’re tasked with rescuing or healing the patient, but because they carry tremendous power and must use it safely and carefully. Let’s examine some of the ways an emotionally abusive therapist might act, and how their actions can harm their vulnerable patients.

1. Forcing trust and demanding disclosure

When a therapist expects unwavering trust, they override the patient’s autonomy and safety in service of their own ego or agenda. If the therapist sees themselves as inherently safe and trustworthy and demands, however covertly, that their patient sees them that way too, they’re ignoring the impact of trauma on the patient. They’re also bypassing their responsibility to carefully monitor and attend to normal fluctuations in the patient’s level of trust.

Trust is built and earned, and it can easily shrink or diminish. Possibly because of missteps by the therapist, or because of what’s going on in the mind, body and life of the patient throughout the course of therapy. The patient demonstrates trust in the therapist through the very act of showing up and sitting in front of another person—a stranger, in many senses—to reveal some of their deepest and most uncomfortable thoughts and feelings. When a therapist doesn’t respect this and keeps demanding more from the patient, they pressure the patient to ignore their own instincts and needs and submit to the therapist and their supposed benevolence instead.

In every relationship or situation, we have a right to avoid certain topics and keep some things to ourselves. Some people are safe enough to talk about X with, for example, but we wouldn’t discuss Y with them. That’s normal, and it applies in therapy, too. When a therapist forces a patient to trust them, especially without having earned and maintained that trust, and they push the patient to share details about their lives or trauma too soon or at the wrong time, the patient can end up destabilised and retraumatised. Trauma processing should happen slowly and carefully, with a safe and trusted other, or not at all.

2. A need for control and authority

Therapy should centre the patient’s needs and goals, empowering them to trust themselves first. When a therapist decides they know what’s best for the patient, or they ignore the patient’s priorities and push their own agenda, this can limit the patient’s autonomy, self-trust and independence. Similarly, when a therapist pressures the patient, is inflexible in their approach, or expects the patient to submit to their authority and expertise, this can leave the patient feeling frustrated, unheard, trapped and powerless.

Abusive people have a strong need for power and control because it fulfills emotional or psychological needs that they’re unable to meet in healthy ways. Their drive for dominance often stems from deep-seated insecurity or fear. They feel unworthy and inadequate, but instead of facing these feelings, they compensate by controlling others. By dominating the patient, the abusive therapist gets to feel superior, and this can temporarily silence their inner self-doubt. If their control is threatened, they will attack the patient either subtly or overtly to restore their sense of power and superiority.

Some abusive people genuinely believe they are superior to others and, therefore, deserve to have power over them. Some therapists genuinely believe they’re more healed, saintly and wise than their patients and therefore deserve to control the patient and the therapy. They see themselves as heroes, rescuers or martyrs tasked with saving the inferior and deficient patient from themselves. Additionally, therapists exist within a system that grants them credibility, and therapists have perceived authority because of their training and credentials. But the biggest authority on the patient is always the patient themselves, and a therapist who denies or ignores this fact can cause serious harm.

3. Gaslighting, lying or manipulating

If a therapist makes statements, asks questions, or leads the patient in a particular direction and then later denies having done it, that’s gaslighting. If a therapist denies the patient’s accurate perception of them or chooses to protect and defend themselves rather than being honest and accountable for their mistakes, that is also gaslighting. It’s dangerous because it distorts the patient’s reality and undermines their self-trust. It can leave the patient feeling confused, frustrated and unable to trust their own judgement.

When an abusive therapist is out of their depth, or they know they’ve made a mistake, or they feel threatened by the patient’s autonomy or awareness, they may resort to gaslighting behaviours that serve to undermine the patient and protect the therapist’s interests. If the therapist fears being reported or worries that their reputation or livelihood is at stake, they may feel driven—however unconsciously—to attack the patient’s perception. The aim is to reduce the patient’s confidence in their sense of what is happening, or not happening, within the therapy.

Because therapy culture often encourages us to trust our therapists’ knowledge, wisdom and instincts over our own, the effects of gaslighting by a therapist can be particularly damaging. Patients can be left feeling extremely disoriented and battling cognitive dissonance—how can it be that this professional who I have come to trust and depend on is now treating me with such disdain and unkindness? For many of us, the early days of therapy, when the therapist is on their best behaviour, can be the first time in our lives that we’ve felt truly seen, heard and held by another person. When this changes and the therapist turns on us to protect themselves, it can be very hard to validate our own perceptions and find the strength to walk away.

4. Belittling and bullying

When a patient—perhaps unknowingly—challenges the therapist’s ego, self-image or worldview, and the therapist feels threatened, the therapist might respond with bullying or belittling behaviours that serve to undermine the patient’s self-esteem and reinforce the therapist’s power and authority. Rather than self-reflecting and questioning their own narrative or assumptions, the therapist might mock, invalidate or dismiss the patient, leaving the patient feeling small, silenced, shamed and unsure of themselves.

A therapist can belittle and bully a patient in subtle or overt ways. When the bullying is obvious, the therapist might use sarcasm or make fun of the patient’s emotions, experiences or struggles. The therapist might criticise the patient harshly by attacking their choices, personality or intelligence, or comparing them unfavourably to other people or patients. They might also raise their voice, use an intimidating tone, or use facial expressions and body language to overpower the patient during conversations. Less obvious forms of bullying include minimising the client’s experiences or dismissing and invalidating their feelings. Bullying can also look like pathologising the patient’s normal reactions as a sign of mental illness or disordered behaviour.

We tend to think of bullying as something that happens only in childhood, but that is not the case. Many adults are bullies, and bullying can occur across a wide range of settings. Within therapy, bullying can be especially damaging because the patient is in an emotionally vulnerable position. Therapy should be a safe and supportive space where the client feels valued and respected by the therapist. But bullying behaviours create fear in the victim and elevate the power of the person doing the bullying. It can leave the patient feeling severely anxious, depressed, trapped and even suicidal.

5. Withholding warmth and positive regard

It’s normal to want to feel seen, accepted, supported and made safe by the therapist. If a therapist only shows warmth and affection when the patient agrees with them, complies with their agenda and meets their ego demands, this can leave the patient feeling desperate to please the therapist and win back their approval. It can cause the patient to abandon themselves and their interests in service of meeting the therapist’s needs and regaining their support. Additionally, it can be very hard for patients to break free from a dynamic like this.

Early on in their training, therapists are taught to offer unconditional positive regard to their patients. This means they should show complete support and acceptance of the patient no matter what the patient says or does. Humanist psychologist Carl Rogers coined the term to describe a technique he believed to be essential in person-centred therapy. Many of us didn’t receive unconditional positive regard during childhood. We were regularly punished, shamed or attacked for not aligning with or pleasing our parents or other adults in our lives. Therapy, then, offers us a second chance. If we are accepted and supported by our therapists unconditionally, it is believed that we can develop the self-acceptance and self-worth we weren’t able to develop during childhood.

When a therapist withholds warmth and fails to offer unconditional positive regard, the negative messages the patient received about themselves in childhood or during other parts of their lives are reinforced. Instead of growing in self-acceptance and self-worth, the patient’s perception of themselves as bad, broken and unlovable can heighten. With it, their anxiety, depression and other negative emotions and experiences can take over. Rather than being a source of comfort, safety and confidence, the therapist becomes another negative voice or critic in the life of the patient, and their hope of ever finding healing and peace can diminish.

6. Projection and projective identification

When a therapist unconsciously projects their issues onto a patient, they transfer their personal struggles, biases or unresolved emotions onto the patient’s experience. Instead of seeing the patient as a unique and separate person with their own reality, the therapist’s interpretations are clouded by their baggage. The therapy becomes more about meeting the therapist’s requirements, and it can leave the patient feeling invalidated, misunderstood, misdiagnosed and burdened with the therapist’s emotional and relational needs.

With projective identification, this goes a step further. Not only does the therapist project their issues onto the patient, but they subtly influence the patient to take on those feelings and interpret them as their own. As an example, when a therapist is anxious about their competence and ability to help, they might project their feelings onto the patient, seeing them as the issue rather than acknowledging their own insecurities. They may label the patient as difficult or resistant and blame them for the lack of progress or any challenges in the work. If the therapist expresses this to the patient—perhaps by saying or implying that the patient is avoidant or difficult to work with—the patient may internalise that and start to feel like a bad person or someone who is beyond help. The reality, of course, is that the problem is rooted in the therapist’s insecurity and inability to deal with their own anxieties.

Therapists are supposed to help patients untangle their emotions and experiences. When a therapist burdens a patient with their issues instead, not only are they failing to help, but they’re adding to the patient's problems. The therapist and their own needs take up too much space within the therapy. Because of the power imbalance and the patient’s lack of understanding, the patient often feels unable to challenge what is happening. The client’s experience becomes distorted, and they can internalise harmful messages about themselves that leave them feeling blamed, confused or broken.

The rundown:

Emotional abuse can occur in any relationship, and therapists are not immune to inflicting this type of harm. When a therapist hasn’t done enough of their own work, they can act out their pain and emotional issues on their patients. This can happen in a variety of ways, including but not limited to:

Forcing trust and demanding disclosure

Fighting the patient for power and control

Gaslighting, lying to, or manipulating the patient

Belittling and bullying the patient

Withholding warmth and positive regard

Projecting their unresolved issues onto the patient

Emotional abuse is an attack on the self, and patients who are abused by their therapists in this way can suffer significant damage. It erodes their trust in themselves and other people and seriously diminishes their self-esteem. Not only does emotional abuse by a therapist prevent recovery and progress, but it compounds the trauma or difficulties the patient brought to therapy in the first place. Recovery can be a long and arduous task.

A note to survivors…

If you’ve experienced emotional abuse in therapy, I want you to know that you’re not alone and you’re not imagining things. It’s real, it’s violent, and it is soul-crushing. You do not have to be a perfect patient to deserve care that is safe and respectful. And, in fact, there is no such thing as a perfect patient.

It can be hard to find validation and support after emotional abuse, and even more so when the abuser is a qualified and licensed therapist. Many people don’t want to see it because they need to believe that help is available and that helpers are good and trustworthy.

I believe you, and I see you. I know how painful emotional abuse can be, and I know how destructive it can be when a therapist inflicts this type of harm. Recovery is not easy, but you can recover from this. You can take back your life. Trust your own perceptions, your own emotions, and your own story. Your abusive therapist does not control your truth. Their distortions do not define you.

Sources and other wisdom:

Chemel, Tasha and Russ, Natalie: Resistance Does Not Exist (2024) - Therapy Harm Resistance Project

Chemel, Tasha and Russ, Natalie: The Four Horsemen of Therapy Harm (2024) - Therapy Harm Resistance Project

Cherry, Kendra: Unconditional Positive Regard in Psychology (2024) - Very Well Mind

Lott, Deborah A.: How and Why Did This Happen to Me? (accessed 2025) - Therapy Exploitation Link Line (TELL)

McLeod, Saul: Psychological Projection + Examples (2024) - Simply Psychology

Spring, Carolyn: Trust is Built (2021) - carolynspring.com

Spring, Carolyn: Who Would You Work With? (2021) - carolynspring.com

Great piece, Sophie! And I love the wider purpose of your Substack - I think we need to talk more about the failures of therapy given the amount of time and money that is thrown at it.

Ugh so validating. I once had a therapist who rolled her eyes at me.

????!!!!!

Then she had the gall to keep calling me and asking for a “closure session.”

I don’t need closure. You rolled your eyes at me! That’s all the closure I need. I’m out!